Sign up for the Morning Update email newsletter

It was a windy Wednesday in April when the governor gripped his pen. It had been five days since members of the Assembly and state Senate had delivered legislation to his desk. It would return to the other side of the Capitol without his signature, vetoed without remorse.

The bill and subsequent veto were the latest actions in a years-long, contentious fight between the governor and legislators over the reapportionment of the state’s legislative districts. Already the two sides had found themselves in court on multiple occasions, pressing the Wisconsin Supreme Court to rule in their favor about where legislative districts in the state should find their boundaries.

It was 1964. John Reynolds, a Democrat, held the governorship, and both chambers of the Legislature were controlled by Republicans.

Reynolds, 43 at the time, sported round, black glasses that framed his sleepy eyes. He had a receding hairline, which, in tandem with his round chin, made his face a near-perfect oval. Born and raised in Green Bay, the former state attorney general found himself in the second year of his first and only term as governor. It had not been an easy 16-or-so months — having been elected a year-and-a-half ago, he succeeded then-Gov. Gaylord Nelson, the environmentalist perhaps best known for founding Earth Day.

The two Democratic governors had been in an apportionment brawl with Republicans in the Legislature since data from the 1960 census had been delivered to the state. During the legislative session of 1961 and 1962, Nelson vetoed multiple attempts at redistricting from legislators. When Reynolds took up residence in the governor’s mansion, he carried on the tradition.

In 1963, Reynolds vetoed an original set of maps sent to him by lawmakers. In the months to come, Republicans would try to cut him out of the process altogether, passing their maps via a joint resolution, which the governor could not veto.

But Reynolds, a former state attorney general, didn’t give up the fight. He took the Legislature to court — and in February 1964, he won. The state Supreme Court ruled in his favor, declaring that “legislative districts of the state of Wisconsin cannot be apportioned without the joint action of the legislature and the governor.” And the court went further, ruling that the maps the state was using at the time — which were drawn in 1951 — were no longer acceptable because of shifts in Wisconsin’s population.

New maps had to be enacted by May 1, the court ordered, or it would step in and release its own apportionment plan by May 15, 1964. In April, as noted, Reynolds vetoed a final attempt at redistricting from the Legislature.

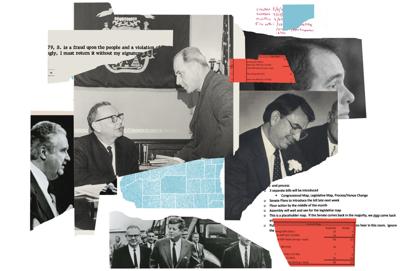

"(The maps are) a fraud upon the people and a violation of their constitutional rights,” Reynolds wrote of Republicans' plan in his veto message. “Accordingly, I must return (the bill) without my signature."

Republicans admitted defeat, and on May 14, the state Supreme Court released its apportionment plan. The fight was settled — for the time being.

Courts have historic involvement in voting maps

Legal battles over the reapportionment process in Wisconsin are commonplace. In fact, there hasn’t been a full redistricting process in the state that didn’t result in some sort of legal action since 1921, according to a report from the nonpartisan Legislative Reference Bureau.

While Reynolds and legislative Republicans kicked off the modern era of redistricting legal fights in the early 1960s, it did not end with them.

In 1981, Republicans and Democrats found themselves in reversed roles. Republican Gov. Lee Dreyfus resided on the shores of Lake Mendota while Democrats controlled both chambers of the Legislature. Democrats passed a plan in May of that year, and Dreyfus vetoed it.

Dreyfus said in his veto message that redistricting is one of the “most important duties our State Constitution entrusts to the Legislature.”

“The concept of a Legislature is that the people are self-governed through elected representatives,” he wrote. “If we place impediments to the people being represented so that they begin to feel ineffective, we are undercutting the survival of not only the state, but the nation, because we undercut the confidence of the people in their ability to actually self-govern.”

“Because of its impact on the political careers of those who must carry it out, it is also one of the most difficult” tasks the Legislature must pursue, he concluded — similar arguments are made by modern-day Democrats.

With deadlines looming, the federal U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin stepped in and established the maps.

1991 was the same. Legislative Democrats were at odds with Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson and a federal court drew the maps. A federal court also drew legislative boundaries during the aughts, as Wisconsin once again found itself in a state of divided government in 2001.

‘Ignore the public comments’

The 2011 reapportionment process is an outlier in Wisconsin history. It was the first time that a governor and Legislature of the same party controlled redistricting since the 1950s, according to the LRB. Then-Gov. Scott Walker signed Wisconsin’s current, gerrymandered districts into law in August 2011 — after what court documents show was a secretive and partisan effort to cement Republican majorities in the Legislature.

So secretive, court documents show, that Republican lawmakers were required to sign non-disclosure agreements before they were allowed to see draft versions of the new maps, and they were only allowed to see the boundaries and projected partisan advantage for their own districts.

Talking points for meetings between GOP lawmakers and a lead Republican legislative aide who helped draw the maps included in a court filing also suggest that there were attempts to mislead outsiders about the gerrymandered nature of the new maps.

“Public comments on this map may be different than what you hear in this room,” the talking points from Adam Foltz, an aide who helped draw the maps, read. “Ignore the public comments.”

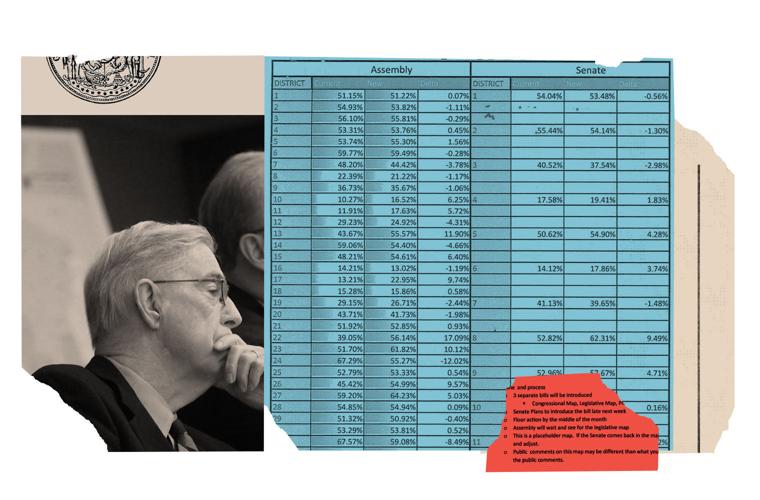

The cloak-and-dagger worked for Republicans. Model maps developed by Foltz and other operatives — which resemble the districts in place today — projected that 52 Assembly districts and 17 state Senate districts would be solidly Republican. That moved 12 and two districts respectively to the GOP, cementing majorities in both chambers before elections in “swing” districts were settled.

The 2011 maps were met by a legal challenge. But barring a small adjustment to two districts, the maps were upheld by a federal three-judge panel.

A later legal challenge threatened the maps. In November 2016, a federal three-judge panel from the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the districts were unconstitutional. The ruling, which was the result of a lawsuit from Democratic voters who claimed the districts “wasted” their votes — a similar argument to that of Dreyfus in his 1980s veto message — ordered Republican lawmakers to redraw the maps in January 2017. GOP lawmakers appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the case was thrown out on a technicality in June 2018.

One year later, the nation’s high court punted on partisan gerrymandering altogether: “We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts," Chief Justice John Roberts wrote at the time — leaving states to navigate redistricting efforts on their own.

Democrats flip-flop on redistricting

During the 2009-10 legislative session, Democrats had ample opportunity to start the years-long process of amending the Wisconsin Constitution to move toward nonpartisan redistricting. They had narrow majorities in both chambers of the Legislature and a Democratic governor in Jim Doyle.

One joint resolution that would have inched toward nonpartisan redistricting was introduced that session, but it gained the support of just five Democratic lawmakers in the Assembly and a single senator — despite their control of both houses.

Assembly Minority Leader Gordon Hintz, D-Oshkosh, was among the lawmakers who supported the joint resolution.

He told the Cap Times in a recent phone interview that the resolution didn’t gain more traction because Democrats were new to the majority and focused on shepherding the state through the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

“Leave it up to Democrats to be super focused on public policy and representing their districts and not enough on power and control of the future,” Hintz said. “In some ways we were consistent with our brand, I guess.”

Others, like former Democratic state Sen. Tim Cullen, a nonpartisan redistricting advocate, sees it differently.

Power, he said, prevented Democrats from starting the process.

“Power is a tough thing to handle,” the Janesville native said of Democrats’ plans in the late aughts to gerrymander the maps in their favor come 2011 instead of implementing a nonpartisan redistricting plan akin to the process in Iowa. “People get it. They want to use it. And that’s usually not in the public interest.”

Instead, liberal lawmakers would find themselves powerless in the next Legislature.

Wisconsin was among several states in 2010 where a nationwide Republican surge allowed the GOP to recapture the Legislature as well as the governorship.

Realizing their sudden helplessness in the reapportionment process, Democratic lawmakers made several failed attempts in 2011 to modify the state’s redistricting methods. They ranged in scale and scope — many of them would have required amending Wisconsin’s constitution — and all failed to gain support from Republicans who were busy drawing news maps to solidify their control of the legislative branch.

One proposal, put forth by Cullen, would have given an independent commission control of the redistricting process. Under the plan, the independent commission would have drawn the maps, which then would have had to be approved by voters via a referendum. If voters rejected the maps, the duty of reapportionment would have been left to the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The proposal failed to pass — but had it been enacted, the commission would have taken over redistricting for the first time starting this year.

“The idea that you can guarantee yourself a job for 10 years by casting one vote, really is pretty outrageous,” Cullen said of the current redistricting process and the seeming conflict of interest it creates for legislators.

He added: “Neither party is holy on (redistricting). It's all about power. And if you got it, you abuse it.”

Former state Rep. Fred Kessler, also a Democrat, put forth another plan that would have established competitiveness criteria for each district, according to the LRB. It, too, failed.

A third package introduced by Democrats in 2011 would have required the nonpartisan Legislative Reference Bureau and former Government Accountability Board to draw the maps and submit them for approval by lawmakers. The pattern of unsuccess continued.

Even still, nonpartisan redistricting wouldn’t guarantee a competitive battle for control of the Legislature. Take Michigan, for example, where voters approved by a wide margin a proposal to create a nonpartisan redistricting commission in 2018. Despite Democrats’ apparent gains in the state in 2018 and 2020, analyses of the commission’s proposed maps still show that Republicans will maintain a meaningful edge in the statehouse in Lansing.

Democrats’ silver bullet might not be so silver.

2021 legal battle underway

Successful legal challenges to legislative and congressional districts in Wisconsin have been focused on the principle of unequal representation, not competition. Put another way, courts are more prepared to strike down maps whose districts do not contain an equal number of people, rather than ones that favor one party over the other.

That’s the approach that three different lawsuits already filed in 2021 have adopted. One of the lawsuits, raised by the conservative Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, was filed as an original action with, and accepted by, the Wisconsin Supreme Court. The other two, brought by the liberal legal groups Democracy Docket and Law Forward, were filed in federal court.

All three suits assume that the Republican-led Legislature and Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, will fail to reach an agreement on a new set of maps.

Assembly Speaker Robin Vos has been adamant that the courts won’t need to be involved in the redistricting process.

“Soon we will begin the robust map drawing process and I’m confident we will draw a map that the governor will sign,” the Rochester Republican said in August. He said Tuesday that the Legislature’s goal is to pass a redistricting plan before it goes into recess Nov. 11.

However, a recent joint resolution from Republican lawmakers in the Legislature which proclaimed that the new districts should “retain as much as possible the core of existing districts,” was met with ire from Evers.

“The current maps are inadequate,” Evers told reporters during a news conference at the World Dairy Expo last month before lawmakers passed the resolution. “To base our decision making on that inadequacy would be not doing the people’s work.”

The lawsuits already filed this year also argue that, in light of data from the 2020 census, that existing districts are malapportioned.

Given their similarities, the two federal cases were consolidated in front of an already assembled three-judge panel procured by 7th Circuit Court of Appeals Chief Judge Diane Sykes. The panel consists of two judges nominated by former President Barack Obama and another tapped by former President Donald Trump.

Earlier this month, after the Wisconsin Supreme Court last month made the unprecedented decision to take original jurisdiction over the case brought by WILL, the federal three-judge panel paused its case until at least Nov. 5. The state’s high court, if it wants to, does have “first dibs on drawing the lines,” said Robert Yablon, a UW-Madison law professor and expert on federal courts.

“There's precedent from the U.S. Supreme Court that indicates that federal courts should essentially let the state courts give it a try first,” Yablon said in an interview. “And as long as they're acting in a timely way, the federal courts aren't going to step on their toes. The federal courts will kind of be there as a backstop.”

The federal court insists that it is prepared to take on the case if necessary: “Federal rights are at stake, so this court will stand by to draw the maps — should it become necessary,” the judges wrote in their order freezing the lawsuit.

Yablon also noted that the involvement of federal law complicates these cases. He said that even though plaintiffs in the case before the Wisconsin Supreme Court framed the issue around the Wisconsin Constitution, others involved in the case, because of its similarities to the federal lawsuits, might try to have the case removed from the state court to the federal court.

The liberals on the state’s high court, who find themselves in a 4-3 minority, also questioned whether or not they should be addressing redistricting.

In the order taking original jurisdiction over the case, Justice Rebecca Dallet, on behalf of her liberal colleagues in her dissent, proclaimed that “now is not the time and this petition is not the way” for the court to consider reapportionment.

She wrote that redistricting fights should be handled by federal courts — as they have been over the last 40 years.

“The majority’s order charts no course whatsoever,” Dallet wrote. “It drops the court into the redistricting wilderness without even a compass. The order sets forth no plan for how seven Justices with no experience in drawing district maps should go about this Herculean task while simultaneously attending to the rest of the court’s docket.”

“Although I trust my colleagues as jurists, I do not share their confidence that we can simultaneously be legislators, cartographers and mathematicians,” she concluded.

Who draws the maps, and how they draw them, could bear great consequences for Republicans and Democrats alike. If the maps are redrawn on a nonpartisan basis, as Evers has pushed for with his People’s Maps Commission, or even a less partisan basis, it could threaten the GOP’s decade-long grip on the Legislature, said David Canon, a UW-Madison political science professor and expert on the redistricting process.

“There's a chance that if you just bring the map back to being an average partisan gerrymander, rather than one of the most extreme outliers in the last 50 years … that would lead to a net pick-up of a handful of Democratic seats that could at least put the Senate in play,” he said in an interview.

During the state’s 2020 legislative elections, Democratic candidates received roughly 46% of all votes in Assembly races, while winning just 38 of 99 seats. Democrats running for state Senate earned 47% of total votes, but only won 12 of 33 seats (though not all senators ran for reelection in 2020).

Legal uncertainty aside, expect this much: Republicans will draw the maps, Evers will veto them and a court will redraw the districts.

Historically speaking, that’s the Wisconsin way. At least, John Reynolds would have said so.